Makah whaler Wilson Parker posing as a MAKAH WHALER for Edward Curtis, ca.1915

The magazine of Washington State University has a nice article on the archaeological project at Ozette, the UNESCO World Heritage Site on the west side of the Olympic Peninsula. This Makah village site was covered by a landslide about three hundred years ago (animation), which created preservation conditions highly favourable to preservation of wooden artifacts. The story begins

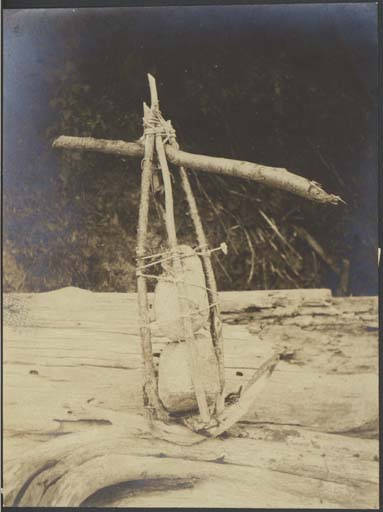

THERE’S A WELL-KNOWN PHOTOGRAPH taken by Native American chronicler Edward Curtis in 1915 of a Makah whaler. Dressed in an animal skin, the man is longhaired and wild. He had indeed been a whaler, as had generations of his people. But still, the photograph is a memory of a time already past. Curtis provided Wilson Parker with a hide and a wig to replace the European clothes the Makahs had adopted long before. In spite of Curtis’s fiction, however, there is much to be learned from Wilson Parker, the man in the photograph. As is always the case with a good myth, there is a deeper truth that lies beneath the surface story.

Parker is Sharon Kanichy’s great-great-grandfather, she tells me as we talk in the Makah cultural center in Neah Bay. Kanichy ’01 was born in February 1970. That same month, a powerful storm blew in off the Pacific, eroding the bank above the beach at Cape Alava, on the Olympic Coast, revealing something remarkable.

“All we knew was there was a burial site,” says Ed Claplanhoo of the buried longhouses revealed by that February storm. Claplanhoo ’56 was Makah tribal chairman in 1970, so it was he who got a phone call the first Saturday in February, from a hippie schoolteacher, as Claplanhoo describes him. A dubious character, says Claplanhoo, which is why he didn’t take the fellow seriously when he tried to warn Claplanhoo that “people” were getting in the “house” and taking “artifacts.” Claplanhoo knew everyone in Neah Bay and knew everyone who owned artifacts. He’d heard of no problems.

But the fellow persisted. The next Sunday, the same phone call. “Mr. Claplanhoo, they’re still taking artifacts out of the house.”

“So I said okay,” says Claplanhoo, “I’ll tell you what, you come to my house at seven o’clock tonight and we’ll talk about it.”

From there, the article recounts the story of the Ozette excavations from the point of view of both Makah and the archaeologist Richard Daugherty, who led the decade long excavation of “North America’s Pompeii.” It nicely captures the importance of the site as well as the nature of the dig and the social relations formed which endure to this day.

Don’t miss the slideshow from the excavations — it’s an awkward interface but some very atmospheric pictures of life on a remote archaeological dig in the 1960s – as well as a few shots of the US Marines who helped airlift supplies in and treasures out.

Digging at the Ozette Site - the hoses were used to gently free the wooden artifacts, such as the house planks shown, from the mudflow which buried them. Source: WASU Magazine.