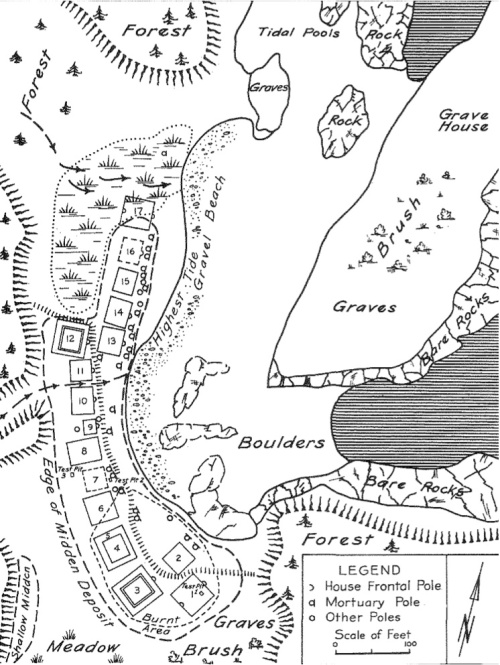

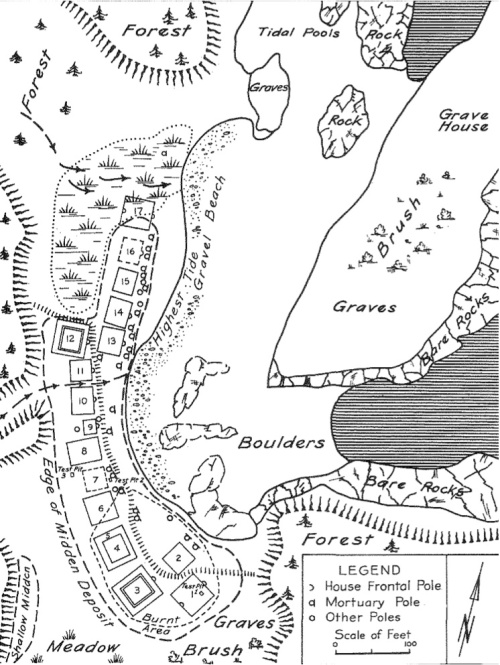

Map of SGang Gwaay Town. Duff and Kew, 1957

As promised, I am linking to a copy of the 1957 report (PDF) by Wilson Duff and Michael Kew on the Kunghit Haida town of SGang Gwaay, which has also been known erroneously as Ninstints. Little mention is made of the pole recovery aspect which was the subject of previous posts, though if you scroll all the way down in Duff and Kew’s article I append Duff’s report from that same issue of the “Report of the Provincial Museum of Natural History and Anthropology”. In that report, the personnel involved are noted and there is also a discussion of the activity of the “B.C. Totem Pole Restoration Committee.”

Anyway, Duff and Kew describe in full the environment and setting of Anthony Island, the town site and associated archaeological sites, and also gives a full account of the early period conflict between Haida and trading ships. In particular, vivid detail is given of the rise and fall of Chief Koyah and the serial raids he led on trading ships. As Duff notes, this escalation in violence may well have been the resulted of an ill-advised power-play by Captain Kendrick who temporarily held Koyah hostage, a mortal insult in Haida society:

What Kendrick regarded as a simple” lesson” must to Koyah have been a monstrous and shattering indignity. No Coast Indian chief could endure even the slightest insult without taking steps immediately to restore his damaged prestige. To be taken captive, even by a white man, was like being made a slave, and that stigma could be removed only by the greatest feats of revenge or distributions of wealth. This humiliating violation of Koyah’s person must have been shattering to his prestige in the tribe. The Indian account of the incident told to Captain Gray a year later (but before Gray had heard Kendrick’s version) states this very clearly.

“On Coyah the chief’s being asked for, we were informed by several of the natives . . . that Captain Kendrick was here some time ago . . . that he took Coyah, tied a rope around his neck, whipped him, painted his face, cut off his hair, took away from him a great many skins, and then turned him ashore. Coyah was now no longer a chief, but an ‘AWiko,’ or one of the lower class. They have now no head chief, but many inferior chiefs. . . .” (Hoskins, in Howay, 1941, p. 200).

Kendrick had hurt Koyah more than he knew. On Koyah’s part, if we understand the motivations of a Haida chief correctly, only bloody revenge or a great distribution of wealth would restore his lost prestige. To capture and destroy Kendrick’s ship, for example, and then distribute the loot, would fill the bill nicely. Koyah watched for his chance, and John Kendrick’s carelessness soon gave it to him.

Continue reading →