I’m probably the last person to get the memo that you can fire a harpoon with a bow and arrow. In fact, I only just got my head around firing a harpoon with an atlatl. Anyway, take a squint at the picture above – the figure in the lower left background is clearly shooting a harpoon-arrow from his bow. The picture is from about 1850 and is a pencil drawing of a scene at The Dalles, on the Columbia River. I’ll take a closer look at this picture below.

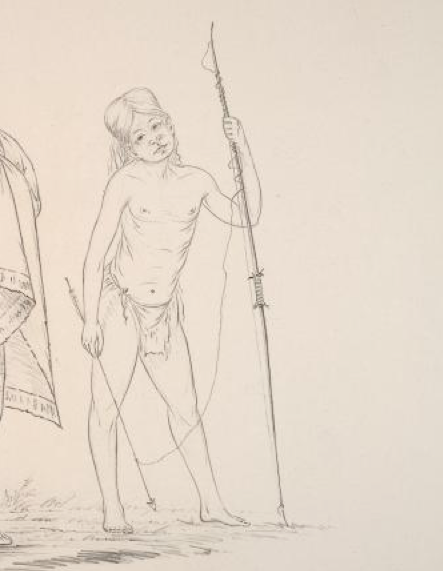

Detail showing use of arrow-harpoon at the Dalles. Pencil drawing about 1850, by George Catlin. Source: NYPL

In the detail above, you can see more clearly that the boy is standing on a rock above an eddy, aiming straight down. Presumably the tactic is to wait motionless until a fish swims underneath, allowing him to aim with less concern for the refraction of the water. Then the typical advantages of the bow and arrow come into play: high velocity and an almost motionless release (slight motion of fingertips) allow the fish precious little time to react before it is skewered.

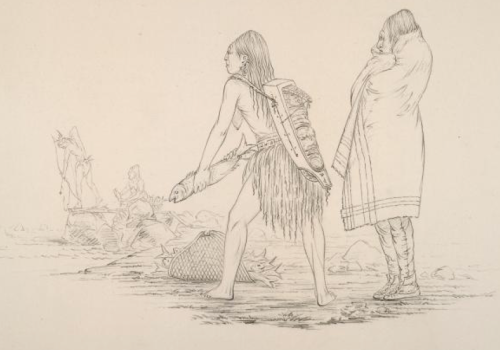

The full text of the caption for the above image is:

Flat Head. Hoogst-ah-a, second chief of the tribe, with a blanket wrapped around him; A Flathead woman, wife of the Chief, basketing salmon, at the Dalles, on the Columbia River; A Flathead boy, shooting salmon with his harpoon arrows, as they are passing the Dalles.

The picture is a pencil drawing by George Catlin, a well-known 19th century artist of the west, especially those showing Native Americans. It is from one of his lesser known books, the magisterially-titled (yet apparently self-published) “Souvenir of the N.American Indians as they were in the middle of the Nineteenth Century, A numerous and noble Race of Human Beings fast passing to extinction leaving no Monuments or Records of their own in existence”. That’s a mouthful, mostly of balderdash. If you don’t happen to have your copy handy, you can view the whole thing at the New York Public Library website here. The NYPL website actually has a lot of interesting documents on file including scans of rare books, postcards, ephemera and the like. I’ve got tons of bookmarks to materials from it. The new beta search engine is good, but the old one is somewhat simpler to use and easier to access captions – work outwards from here, for example. They also allow searches to be persistent – I bookmarked this page over three years ago and it still works.

Detail of the boy Yun-ne-yow with the arrow-harpoon. 1850 pencil drawing by George Catlin. Source: NYPL

Anyway, in the above image detail (original here) you can see the same boy, identified by the name “Yun-ne-yow (the Green Vine the Creeps[?])” posing with his bow and harpoon-arrow. The lanyard is attached to about 1/4 of the way along the arrow from the tip, and is tied off at one end of the bow. He has it sort of casually wrapped around the bow presumably as a way to keep from tripping on the lanyard — it’s a nice human touch. I’m calling this rig a harpoon even though the arrow-head doesn’t detach, if any of you weapons types wants to correct me then go ahead. Basically it is an arrow with a string tied onto it and shows that you don’t always have to overthink your technology.

An interesting aspect of this system is that archaeologically, we might normally only recover a stone “arrowhead”, and ascribe it perhaps to land-mammal hunting. It’d be a bold archaeologist who started routinely cataloguing small triangular, stemmed or side-notched late period flaked stone points as harpoon-heads! But, if memory serves me well, some of the famous sites at the Dalles are chock-full of small “arrowheads” – as in, ridiculously high densities of these. Virginia Butler quotes an estimate that one collector dug up over 150,000 of these. I’m not really a bold archaeologist so I’m going to leave it at that.

If know a lot about the Dalles, have an opinion on harpoon-arrows, or are just pretty bold, then feel free to add some comments below.

The full text of the caption of the above picture is:

Flat Head. Ya-tax-ta-coo, a Flathead (Chinook) warrior; Yun-ne-yow (the Green Vine the Creeps), a boy with his salmon bow; Chinook woman, with her infant undergoing the process of flattening the head.

Now you might be wondering if such a device would actually work, and as usual in this modern age, dear reader, the answer lies on Youtube.

Goodness, some Yupik hunters still use atatl launched harpoons to catch seals. My father-in-law did. He used an atlatl to launch a 3 pronged dart at geese and swans whenever he ran olut of shotgun shells well into nthe 80’s. A seal dart consisted of a barbed point-ivory or antler that freed itself from a light shaft. A line that was wrapped around the shaft was nconnected to the point. Ihe line would unwind and allow the shaft to act as a drag. Sometimes an inflated bladder was attached to the shaft. The impeded wounded seal would be killed by the hunter in a qayaq racing the shaft as it left ripples in the water. A lance or club would be use to finish off the seal. Ring seals would be the target of the dart. I still carve the atlatls and the occasional dart for people. An atlatl is preferred tor small seals up to 50 yards and is better than the bow and arrow, because it can be launched one handed. while the qayaq is steadied with the other hand and paddle. The Aleuts and Alutiiqs used a harpoon arrow launched with a bow to hunt sea otter in the historic period. They hunted in pairs and one man fired and the other steadied the qayaq. The atlatl continued to be use into the 1940’s on the AK Pennisula. A friend posseses his father’s atlatl. Contact me if you have questions. richardwisecarver@yahoo.com

LikeLike

Hi Richard, Thanks for the vivid info and fascinating the practice continued into the 1980s. My mental block with these gadgets has always been that the retrieval line would get in the way of either the bow or the atlatl, but that just shows the value of my armchair opinion. And no doubt from a kayak an atlatl is preferable to a bow and arrow for the reasons you mention. This is a vivid 1929 photo of the action:

LikeLike

In our book Homeland, we demonstrated that basic, Ishi-type bows could effectively dispatch living bison with Paleoindian project points mounted on arrow shafts (at distance of 20 yards). Our conclusion is that “size doesn’t matter” and we sometimes make wrong assumptions about atlatl v.s. bow projectile points.Good to see the Catlin direct historical approach.

LikeLike

As a kid and a teen I was involved in archery competitions and, although I stopped at the age of 16, I bow-hunted and bow-fished. I had a home-made spool attached to the bow, facing forward and strung with cord fishing line (not monofilament). Attach arrow, shoot same — and the line unwound from the reel/spool. I thought I was a genius for “inventing” this until I discovered that bow-fishing was common, especially along the St. Lawrence.

LikeLike

Nothing new under the sun Mike!

LikeLike

Thank you for the site info. I have enjoyed doing research on line – now that is a whole new world. What we discover in those old archives is a treasure. And thanks all others for your responses too; I saw this kind of bow fishing up around Hazelton as a kid.

LikeLike

Marcia, Larry, Mike: thanks for your comments.

Larry – you are no doubt aware of the emerging evidence from the ice patches which shows fairly conclusively that atlatl darts were all sizes and were mounted with an unexpectedly diverse set of projectile tips (especially considering the target species was likely almost all caribou). I saw a recent poster at a conference on some Wyoming or Colorado ice patch technology and I’ll see if I can dredge up a copy — foreshafts over a metre long with a little stub of fletching! Almost like an opposites-day game.

LikeLike

Yes, I have seen Craig Lee and Bill McConnell’s constructions.

Bill has pretty much perfected the foreshaft composite system for hunting.

LikeLike

Doing survey work on the Columbia Plateau, I was told that points even an inch long were “not arrowheads” as they were too big. This drawing, unless Catlin enlarged the point for artistic purposes, seems to be around that “too big” range. Another bit of fieldwork hearsay, bison kill sites from the Great Plains had points that were called “bird points” (i.e. about 1.5-2 cm), the idea being that the smaller points were more likely to pass between the ribs.

LikeLike

I think “bird points” were named as such because some people thought they were small for shooting birds. We found “bird points” effective in out study with Ishi bows on Tom Brokaw’s bison (see Homeland: An Archaeologist’s View of Yellowstone Country’s Past).

LikeLike

This is an interesting post and reminds me of the debate in the literature of the southern PNW regarding the use of concave based stone points–Lyman and Hildebrandt were the major folks in the dialogue. Ethnographically the smaller of these points were used to tip harpoons for salmon, the larger ones for marine mammals…so the question has revolved around whether this was valid in the past as well

LikeLike

Quentin, if you can find that ice patch atlatl info or post some references or links, it would be much appreciated!

LikeLike

Scott: References for that research. Careful with the Antiquity reference, if you go to Antiquity it won’t be in the journal proper but in another area called the “Project Gallery”. Ice patches are turning up amazing things having to do with the atl-atl to bow and arrow transition, especially in Yukon. The latest can be found in a great volume of Arctic (in which Lee has a paper) edited by Tom Andrews and Glen Mackay (the latter Quentin will be proud to tell you being a UVic grad).

Craig M. Lee, 2012: Withering snow and ice in the mid-latitudes: A new archaeological and paleobiological record for the Rocky Mountain region. Arctic, 65 Supplement 1: 165-177.

Craig M. Lee, 2011: Ice patch archaeology in Yellowstone’s Northern Ranges. In MacDonald, D. H. and Hale, E. S. (eds.) Yellowstone Archaeology: A Synthesis of Archaeological Papers on the Prehistory and History of Yellowstone National Park: Volume 1, Northern Yellowstone. 132 143.

Craig M. Lee, 2010: Global warming reveals wooden artefact frozen over 10,000 years ago in the Rocky Mountains. Antiquity, 84(325).

LikeLike

also of note – this specific special issue of ‘Arctic’ edited by Tom Andrews and Glen MacKay (aka, the famous UVic alum) appears to be downloadable and open access now that their subscribers got a year to absorb the papers and the patches absorbed some more sunlight… congrats to the contributors

http://arctic.synergiesprairies.ca/arctic/index.php/arctic/issue/view/267

LikeLike

This is a good source too:

Hare, P. Gregory, S. Greer, R. Gotthardt, R. Farnell, V. Bowyer, C. Schweger and Diane Strand, 2004. Ethnographic and Archaeological Investigations of Alpine Ice Patches, Southwest Yukon, Canada. Arctic 57-3: 260-272.

Also, in this same volume I am pretty sure, is a study of the feathers used for fletching on the darts and arrows.

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

I can’t resist because Mike’s post brought back memories. As a kid I always had a slingshot, my favourite, which I still have, is made of moulded fiberglass with a hollow handle (hole at top only) that will hold 1/4 inch shot (stop a rabbit) or smaller BBs. I tried shooting arrows but that didn’t work until I made an arrow rest out of a coat hanger, that would attach to the arms, with a dip in the middle to allow the fletching to pass. I’d tie nylon string to that and get carp in the river, and bullfrogs. Good eating. A pouch full of regular BBs was good for pigeons on the fly. I’d bet regular slings were in fairly common usage in the North American past, once you get the hang of the overhand technique reasonable accuracy is possible. A load of small stones into a flock of birds would be effective, but I never tried that with a sling. If anybody’s interested in making slingshots today, get surgical rubber from medical supply stores, perhaps 30 lb pull from that stuff, about the same as a simple self bow.

LikeLike

Growing up in Canada in the 50’s and early 60’s we were a bloodthirsty lot. At 9, living in North Bay, I actually had a snare line with another boy and the two of us went out into the bush on snowshoes for hare. We lived on bushlore and if we could work out ways to do this it simply demonstrates an ingenuity our distant ancestors would have had to a much more heightened degree — out of sheer necessity. I very much doubt that childhood would have been the helpless, parasitic, dependent state of affairs it is today; everyone would have played a part because survival odds increased accordingly. Regrettably, where bow-fishing and other pursuits were concerned, the materials that would have been employed simply didn’t survive in the archaeological record. I wonder how much else we’re missing….

LikeLike

Mike, not sure how to get your personal email from this blog so am using valuable intellectual space here maybe, but similar childhoods, me in Trenton, snare line out back of the elementary school in Grades 7&8. Walking around with rifles was no problem, the magic age for that was 12. Everything I shot and snared we ate. Well, just about everything… We’re not good at recognizing children in the archaeological record, though some have tried. Bob Dawe makes a good case that at least some of the many tiny arrow points at Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump were made by kids. Also I agree that people of the past had ingenuity that we can only begin to imagine and of that, only a bit is preserved in the material record. And they were tough.

LikeLike

Yeah, Mad — but we both know what the reaction would be to a kid in the ‘hood with a weapon today: SWAT time. One cultural horizon’s skillset is another one’s nightmare.

LikeLike

I’ve spent some time wondering if some of the chipped stone hafted bifaces during the Late Period might be the arming elements for composite harpoons, but as I believe Carlson points out in his chapter in his 2008 volume the thickness doesn’t match with the slots of the bone and antler harpoon valves found in most assemblages.

Whether smaller ground stone points can be argued to have been used as harpoon arrows, or simply heavily retouched is another issue. It is possible that uses changed drastically during the life history of an object however…

LikeLike

Hi Adam, thanks for your comment. What does fit those slots then if not the little flaked triangular points? Ground slate ones tend to be pretty thick. Mussel ones are pretty rare, though of course recovery and recognition is poor. Some of them take cylindrical bone points of course, cf. Shannon King thesis. But the slotted ones … yeah, ok, it’d be good to know more. Thanks for pointing me to Carlson – that’s the NW PP volume from SFU press, right?

LikeLike

I have not seen the slots but slate sounds right. Check out Yupik, Inuoiat or Thule harpoon. Check out Ford or the Smithsonian collection. I have several slate insert points that are 1/16 inch thick and quite capable of piercing the skin if a 900.lb bearded seal or 2,000 walrus. Native copper is a small possibility. Take a serious look a Edward Nelson’ s The Eskimo Abot The Bering Sea for Yupik technology.

LikeLike

Both Carlson and Keddie in the SFU volume mention issues with inferring function thanks to the ethnographic examples being made out of iron. Or if they were out of stone were produced for Euroamerican/canadians, and so often larger and more stylistically embellished than archaeological ones.

However, just because many of the chipped stone and ground slate points don’t fit into composite harpoon valves (which King does mention several size classes for slots if I recall correctly) doesn’t mean that they weren’t harpoons since all you really need is a line attachment on the foreshaft. The problem is, the lack of archaeologically preserved foreshafts.

Looking at Hoko and ethnographic accounts (Elmendorf accounts of the Twana particularly) wood and bone were also important for arming elements, and I believe in the Hoko report a few were mentioned as refitting rather well with harpoon valves.

Of course the dream solution to all of this would be to get one of those fancy 3d scanners, scan a whole bunch of artifacts in the collections, and use a 3d printer to make some copies to do experimental archaeology with different types of foreshafts…

LikeLike

a snippet in reference to foreshafts, Alan McMillan and Denis St. Claire identify three fragmented bone foreshafts at Huu7ii in Barkley Sound in their 2012 SFU Archaeology Press publication:

“All three artifacts in this category are fragmentary tapering segments of polished sea mammal bone (Fig. 3-33, lower). They have straight, gradually converging sides and are round to oval in cross-section. The largest comes to a blunt rounded tip at its intact end” pg 53

they further state that:

“Such implements were used as foreshafts on sealing or fishing harpoons. Although many ethnographic examples are of hardwood (Drucker 1951:19, 26; Koppert 1930:65), foreshafts of sea mammal bone are found at most excavated Nuu-chah-nulth sites and are considered one of the identifying features of the West Coast culture type (Mitchell 1990:356). pg 54

McMillan, Alan D. and Denis E. St. Claire

2012 Huu7ii: Household Archaeology at a Nuu-chah-nulth Village Site in Barkley Sound. Archaeology Press, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC.

http://www.sfu.ca/archaeology/archpress/catalogue/huu7ii.html

LikeLike

Thanks Adam and twoeyes. Adam, not sure what you mean — the composite toggling harpoon (CTH) valves have a socket which would go into the harpoon I think, not onto a detachable foreshaft. That is, they are not attached to the foreshaft, but to the line (lanyard). So the problem remains of whether the small triangular chipped or ground points could attach to a slottted CTH.

King’s thesis is here:

http://summit.sfu.ca/item/8311 but her topic is bone points so I don’t think she gets into slate or flaked stone much. I don’t have time to revisit it at the moment.

I think a lot of the examples she had were not slotted but had a groove (a “channel” in the typology) to receive a cylindrical bone point – her abrupt-tipped category, often with impact fractures. This was her strongest result in terms of making sense of the continuum of bone points!

On the other hand, she has the illustration below of two slotted points armed with wedge-based cylindrical bone points, which may answer the ultimate question of what fits into the slotted CTHs. These two were found close together and are interpreted as the arming points of a double-headed harpoon-leister probably for fish.

https://qmackie.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/king-thesis-screenshot1.png

(I lied I revisited it a little bit. Damn pile of marking beside me)

LikeLike

Here’s another in situ composite toggling harpoon head, this one from Tla’amin Territory (Sliammon – “Sunshine Coast” area) as described in a previous post:

LikeLike