Edit October 2018: Hoko Pictures are now here.

I was talking the other day about how under-represented organic technology is in archaeology generally, and especially on the Northwest Coast, where the old adage is that 95% of the technology was made out of plants (trees, wood, bark, roots, grasses, seaweeds). A classic example of this phenomenon are anchor stones and sinker stones. While some of these stones had grooves or perforated holes (and are thereby very visible and durable in the archaeological record), many may have been made by the more simple, subtle and expedient method of simply wrapping line or basketry around an unmodified rock. When the organic component rots away, as it will most of the time, then the archaeologist has, well, an unmodified rock.

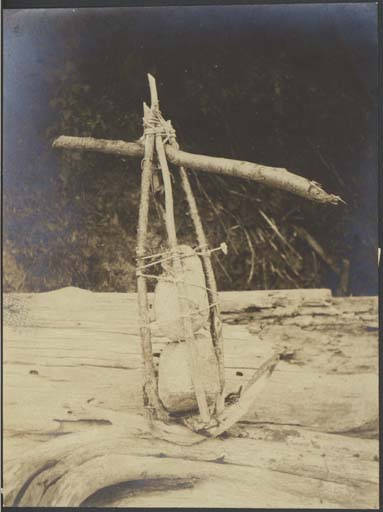

Anyway, it was a lucky stroke for my current interest that I came across the above photo from the University of Washington Digital Archives.

The makers of this anchor stone appear to have come to a similar solution to, or been inspired by, an Admiralty pattern anchor. Anchors achieve a great deal of their holding pattern from the chain rode, which lies on the bottom and acts as a shock absorber. It would be interesting to see how this one works, though if it was intended for a canoe with low windage it might be very effective.

Equally, I wondered about Reef Netting, which requires a lot of heavy anchor stones to be put down, to tighten the canoe position against in this high-precision fishing technique. The operating assumption has been this requires that a large number of sacrificial rocks (i.e., multiple rocks are sent down a single anchor line, making a composite too heavy to pull back up), but it seems to me this Duwamish design might “dig in” and not just be a heavy weight. Admittedly, Norm Easton found a large number of anchor stones underwater at reef netting sites near Victoria and in the Gulf Islands – so there was net loss. (You can get his excellent UVIC thesis here, via here which has a lot of other Eastonian output). But in any case, the above is the most elaborate composite anchor from the NW Coast I’ve seen, I think.

Anyway, more ancient anchor stones and net weights are known from some archaeological sites, notably Hoko River. Once again I recommend the remarkable online photo archives put together by Dale Croes and his team for that site – home page here. I’m reproducing a couple of images here of ca. 2,500 year old wrapped, unmodified rocks – you can view more here. These artifacts at least have a stone component – browse around on the Hoko River photo site and see just how few of the artifacts would leave any trace at all: most of them. Kind of sobering, and that bugs me, because sober is my least favourite word!

Quentin: Maybe that is why wet sites have not caught on?? Too sobering??

Certainly cannot be that they are too expensive or technically involved if we can do 11 seasons of this kind of work at Qwu?gwes from a Community College! I can only conclude that it is generally not part of our field’s learning tradition yet….though should be on the NW Coast–I am sure that every sizable site on the NWC has a wet component, IF we looked for it. At Qwu?gwes we had no reason to believe it included a wet site until we tested the site (and it is a small midden site).

You and brother Al were involved in finding the oldest known wet site with braided spruce root cordage and wooden wedges at Kilgii Gwaay dating to about 9,400 BP–showing we should find wet site materials from the earliest periods of Coastal occupation–very cool wet site that should be further explored if possible?

As far as wrapped 3000 BP anchor stones, some of the neatest examples are from Musqueam NE, with a unique wrapping technique, reported by Archer and Bernick and excavated by Charles Borden.

I need to report to you that I had a great talk with Dr. Carl Gustafson about the carved piece of wood, identified by Alex Krieger on a visit to the Manis Site as an atlatl. Carl does not necessarily believe that it is an atlatl, however he is convinced it has been carved and formed. So not only the bone projectile point in the rib, but also a potential carved wood piece 13,800 BP on the NW Coast. Manis is a peat bog, which are common wet sites in other parts of the world, however most of ours are aquifer wet sites, with flowing waters through the deposits, versus stagnant waters as characterizing a bog. However bogs are not uncommon in our region either.

Carl may work with us, especially wood ID specialist Kathleen Hawes, to determine the plant species of this formed wooden object from Manis. We will keep you updated.

Thanks again for bringing up these issues–great pondering…better get back to grading papers though (sobering)….keep up the great work, Dale

LikeLike

Hi, Q!

When I was working at one of the first recognized wet sites (45SN100) in Washington in 1959-60, we found similar bound sinkers in the bottom of the Snoqualmie River NE from Seattle. The work was by the Washington Archaeological Society (WAS), with professional guidance JL Giddings, an arctic archaeologist, who happened to be viisiting the NW. The specimens I am speaking of were plain unmodified water polished, flat, elliptical pebbles, that would look completely natural in a stream bed, except for a preserved bent willow withe covering the outside edges of the pebble along the longitudinal axis, and then securely bound to the willow by stripped cherry bark . These sinkers were accompanied by basketry, cordage, and wooden artifacts also preserved in the river bottom, probably representing a fish weir feature. A microlithic assemblage, chalcedony scrapers and points were also found in streambank deposits above river level, representing other activities adjacent to the wet site artifacts. These sinkers and the other associated artifacts were stabilized by the WAS and were recently donated to The Burke Museum at the University of Washington by Dr. Astrida Onat. I will attempt to send an email.

LikeLike

Dale and Quentin, when I worked for the US Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) a coworker and I discussed the occurrence of Clovis points associated with peat bogs in western Washington, and we took the agency’s soil data and made a map of all the known peat deposits with the idea that we could use that as a start to begin predicting early site locations. What we discovered was that peat bogs and deposits are really common all over the Puget Sound region, so much so that it wasn’t a great start for a predictive model. Unfortunately, most of these deposits seem to be on private land, like the Manis site, and many were or are being mined for commercial peat or dug up to create ponds, as Manny was attempting to do. Many bog deposits on private lands in the San Juan Islands were excavated in the 1970s-80s with NRCS funding to create wildlife and fire ponds, with no archaeology done.

LikeLike

Scott: You forgot to tell the story of how the woman was asked if she had ever found any arrowheads by the SCS representative and she said YES I found my first one in the peat digging pile and went to the “junk” draw with all the knives and misc. items and pulled out the Clovis Pt! Always helps to ask.

Have a great weekend and stay “sober” like Q….Dale

LikeLike

Hi Dale – yes, there should be more early Holocene wet sites out there. IN addition to Kilgii Gwaay. There are one or two other sites around there in the intertidal, with pristine lithics in a sort of brown jelly paleosol under brach sediments, but those don’t yet have known wooden and bone preservation like Kilgii Gwaay. But very sure there must be more. Anyway, early plan is to go back there this summer for more KG fun (maybe you’d care to make a site visit!?). As to the “no tradition of wetsites” thing – yeah, I have wondered about that. With you and Kitty as the best known practitioners there has certainly been an inspiring model set, and with the years of direct undergrad training you’ve been providing – it is more mystifying than if we could just say, “we have no idea such sites are possible” nor “the implications are huge” or “no one to learn from”. It would be good to have a conversation about what exactly is keeping people (largely including myself) from working on these. And thanks for the Manis info.

Hi David – Your comment amplifies Dale’s, that as early as 1959 (which is very early for NW Coast Archaeology) wet sites were being excavated – so how come we still aren’t really maxxing out on their potential? I think that site might be the Biderbost Site(?), in which case some of the material has been placed online already:

https://qmackie.wordpress.com/2010/02/14/ancient-basketry-from-biderbost-site-puget-sound/

Scott – at least one of the Bison antiquus finds around here was also in the context of turning a wetland into a pond for irrigation purposes. And of course so was the Ayer Pond archaeological bison which we discussed a while back.

https://qmackie.wordpress.com/2010/04/24/orcas-bison/

I suspect that these wetlands have a lot of archaeological potential that is not discernible with shovel testing but only comes to light from deep, ancient deposits when perhaps it was more patchily wet and people were doing more things right on the land surface, or doing things which leave durable traces. Of course, there is also the recently excavated but not yet reported Pitt Polder site in BC, where a massive project discovered “wapato gardens” amongst other incredible finds – something like 50 digging sticks, for example, and evidence of a certain level of plant intensification many would find unexpected for the supposedly boring Charles Phase. https://qmackie.wordpress.com/2010/01/18/wapato-camas-tyee/

LikeLike

great post!

here is a key article for those who want more:

Croes, Dale R. (2003) Northwest Coast wet-site artifacts: a key to understanding resource procurement, storage, management, and exchange. In Emerging from the Mist: Studies in Northwest Coast Culture History, edited by R. G. Matson, G. Coupland and Q. Mackie, pp. 51–75. UBC Press, Vancouver, BC.

LikeLike

Thanks twoeyes. I should have asked it more explicitly – am I right in thinking the Duwamish example is unusually elaborate? Has anyone ever seen another one so large and made with so many constituents (two rocks, a central cradle, a bar at the top and a kedge at the bottom). Like I implied, looks like it’s modelled on a metal Admiralty anchor but it would be good to know more.

LikeLike

I wondered what a metal admiralty anchor looks like and found this image on Wikipedia…

LikeLike

Hi twoeyes, I linked one in the post as well – I think I am not making my point very well here. Most NW Coast anchor stones that I have ever seen are basically a rock with a line on it – even the grooved ones or ones with holes are rocks with lines. These count just on the weight of the stone to do the work, and it’s intrinsic drag on the sea floor. This Duwamish one, to my eye, has the top cross-piece designed to hold the anchor at a certain angle to the sea floor, and it has the “flukes” extending from the bottom of the cradle which holds the rocks, presumably designed to snag or to dig into the sea bottom. It is thus a much more highly engineered and subtle a piece of technology than most. Maybe I am looking at it wrong. I’m not saying it looks just like an Admiralty anchor, but that it has the same basic set of technological subunits.

LikeLike

Agreed Q

But rather than an Admiralty style anchor, I remember some stacked rocks in a framework with spiked end ‘flukes’ from my “Boy’s Book of Knowledge” 1957 (or something like that, an esteemed reference; perhaps more likely, “Royce’s Sailing Illustrated”): anyhow, a history of anchor technology that showed an almost identical anchor – maybe even based on that photo, and then (allegedly) developing into the traditional Chinese anchor with a stone stock. Darned if it was could find an image (somehow my original source has been misplaced….). There’s a great one of Arab traditional boats, some with stone anchors, here http://www.catnaps.org/islamic/boats.html,

Love those simple rocks with simple wrapping that transforms a ‘nothing’ into a ‘wow!’. I’ve always wanted to find one, but never have despite working at several dozen wet sites.

LikeLike

If you find your big book of boy knowledge then let us know! That catnaps.org site is amazing.

It makes me wonder, with these wrapped ones in mind, why would anyone ever bother to put a hole through a rock, or to make a pecked grooved around one.

Not to make it all about stone again, but seeing these simple ones, even the stick-braced ones, it does through the analytical ball back into the court of “why the heck would you spend time making a sinker stone with a hole in it?” What are the advantages, contexts of use, cost-benefit analyses of those sinker stones?

LikeLike

Hi Quentin!

* Why not maximize work at wet sites for the prodigious new information to be gained from them?

There really is a constellation of answers, according to priority and perspective. In general: access & ownership issues; site security & safety of investigators; specialized field and lab equipment; expensive cost of investigation, conservation, and study; legal jurisdiction of navigational waters, river and lake bottoms, permitting for shoreline impacts and/or site excavation permits; unknown extent of depth and lateral extension.

Then there are the wet site institutional requirements & costs for conservation, accessioning, and duration of curation, staff training, student labor and recruitment, and lab equipment. Like dry-land archaeological sites, there needs to be some consensus about priorities — if upland site data recovery for reservoir sites may range from 10-30% for total work done, and this needs to be balanced among a set of different site types and time periods, If you add the requirements for wet site investigations, then sacrifices in other categories of study will have to be made. The US, and the globe, is in fiscal recession, so Government financed archaeology is becoming a shrinking priority.

Then, of course, is the important matter of ‘whose prehistory is at stake?’ So far, the major advances in knowledge about wet site content and significance has come form close collaboration with First Nations/Federally recognized Indian tribes.

All of this means that “wet sites” are extraordinary in every sense, and we must be opportunists, seeking partnerships that can in some measure overcome most of the above limitations and reasons NOT to study them. I think it is a matter of professional commitment, priorities, and human values, and up to each of us, accordingly. It is much more than a public awareness issue, and that in itself is a sensitive issue for site security and preservation.

* Anchor Stone question: Q, you speak of “composite anchor stones.” Are you also considering composite fish trips that use anchor stones? In some cases, the same types of archaeological anchor stones could be used for either net fishing from canoes or in riverine and coastal fish traps. In this case, I am not including submerged stone fish leads to enhance fishing, but actual fish traps that require multiple stone sinkers for their use.

LikeLike

Hi David, belated thanks for your reply. I agree that it is up to each one of us to find a way via professional commitment to encourage wet site archaeology – and certainly opportunism is a big part of this. Your roll-call of the reasons why wet site archaeology is hard to do/seldom done would closely mirror my own. And yet, and yet – Dale Croes has been showing for 10 years that wet site archaeology is viable as a field school project (PDF), and that’s from the fairly modest base of South Puget Sound Community College.

What I mean is, he may not have the full institutional resources some of us have, nor the same access to graduate students who often do both the creative, and grunt, work. So at some level, it can’t be that hard.

The complex jurisdictional issues may be a Washington State thing – I don’t think the same applies here in Canada. The need for enlightened partnerships with First Nations/Tribes is essential in both places though – especially viable though since the organics often speak louder and more eloquently to past practices, including the vibrant living traditions of basketry and weaving. In this, there may be more obvious interest and engagement of indigenous groups from wet site archaeology.

Re: your other question: I was only thinking of composite anchors as being a construction that includes both one or more stones, and some sort of organic framework or wrapping – in contrast to those with a hole or grooved girdle. I doubt it is a technical term though, hence possible confustion.

LikeLike

Quentin, Thanks for getting back with me.

* With regard to the neglect of wet sites here in Washington, the regulation of shoreline and submerged tidelands is both State and Federal, so quite complex, and often designed to protect fish and shellfish, so there is often a ‘closed’ biological window of opportunity. Actually, I think of Dale Croes as being the exception in State wet site accomplishments. I have known and worked with him over 30 years, in times more favorable for archaeology, and it is his passion for this prize that drives him. I can think of almost no one else who has overcome most all of the limitations that I spoke of in my previous post. To wit: He secured training and experience with the WSU Ozette Archaeological Project, and learned the benefits of tribal involvement with exposure to the Makah people there; at Hoko River he successfully secured private foundation funding to support his research and used privately owned lands for field & lab facilities; at Swinomish Slough his experienced eye identified another wet site, which he worked jointly with Astrida Onat (Seattle Community College) with the cooperation of the Swinomish Tribe; another wet site was found on the lower Snohomish River east of Everett due to his sensitivity and vigilance; in moving to Olympia at So. Sound Community College he first partnered with Rhonda Foster (Squaxin Island Tribe), and then collaborated with her program in the work at Mud Bay. So his record is long, and shortage of funds or lack of facilities has not stopped his driving quest to secure wet site recognition. I, myself, am daunted by all of the challenges wet site investigations entail, but they have always been in the back of my mind due to the initial work at Biderbost Site on the Snoqualmie River more than 50 years ago. However, I never failed to support wet site studies within my working jurisdiction (25 years with Corps of Engineers). As you point out, their significance is extraordinary, and heavily enriched through tribal participation, and so the work is strongly supported by them, unlike some upland archaeology that seems to always disturb ancestral graves.

* My second comment simply raised the point that artifacts classified as sinkers or anchor stones may sometimes be used in wicker fish traps to weight them down. Since these sinkers often are the same size and shape as sinkers used with nets and seines, but require greater weight to hold the fish trap down, about ~ 8-12 individual sinkers are bound together into composite weights with cordage. Found separately, these items are indistinguishable from those used with nets individually.

Regarding your comment, ‘Why it seems impractical to drill a hole through a rock to make a sinker, or peck a groove around a large cobble, when it may be easier to use fiber or wood more quickly and easily.’ Both Dale and I took classes at U Washington from Dr. Erna Gunther concerning various technologies employed by pre-contact NW Coast peoples. She was a specialist in NWC basketry and ethno-botany, and, as Director of the Museum at UW, she used a hands-on approach with students with all manner of NWC artifacts made of wood, fiber, stone, bone and antler, and the methods and tools used to make them. I distinctly remember her saying that many large or complex items that would seem impractical to make, were produced during long winter months when it was also impractical to be outside in the storms. Basket making, she said, uses many fiber elements that require seasoning in order to use in a basket, or decorate it. These fiber elements sometimes require acquisition at different seasons of the year. In the winter months, with time on their hands owing to accumulated food surpluses and secure housing, and with the necessary materials at hand, the baskets and mats were made, slowly, bit at a time, while socializing or between mid-winter spirit dances. If there was an immediate need, it was always possible to improvise, using unmodified rocks, using wood, fiber or cordage to secure a net sinker! Of course, NWC peoples also had and made use of slaves for this purpose. In the final analysis, making these impractical kinds of tools was a cultural choice, and also fit the ‘rhythms’ of NWC seasonal rounds and ceremonials, like the potlatch. I am certain that some of the inspiration behind Dale Croe’s early focus on wet sites was as much Erna Gunther as it was the Ozette experience.

LikeLike

I don’t buy the simple ‘because they had time on their hands in winter’ argument. Certainly consuming stored foods in winter allowed for making complex things and there may have been some pride taken in the perversity of doing things the hard way. But I think that most such manufactured things had social messaging behind them and tended to be things that could be on either displayed directly, or at least reflect well on their owners, like a nicely-made though utilitarian clam basket. You’d have to be very unlucky to loose a clam basket the first time you used it.

I can’t see that anyone would spend a lot of time on making a fishing weight perfectly discoidal and centre-perforated. Weights were very likely to be lost (and yes, halibut hooks were too and yet they were often beautifully carved; but I suspect this was to get spirit help and the hook was the ‘business end’ of the system). Is there good evidence for the perfectly circular, parallel-edged pecked and ground discs to actually function as fishing weights? I confess to being rusty on my central/northern ethnographies. Pecking a ‘stirrup line’ or perforation around a convenient sandstone rock for a fish weight is no big consumer of time, and is probably similar to the effort used to make a cordage net or wicker enclosure for it. But I’m thinking of the basalt things that look like ‘bar bell weights’ found on the northern coast. Sometimes these are completely finished otherwise but are unperforated.

There were games and pastimes which used unusual equipment. Teit lists many games, often with stone balls, or composite discs rolled as targets, for the southern Interior Salishan groups. Perhaps the coastal stone discs were also used in some type of game?

LikeLike

Pingback: No Flake / unmodified litho artifact

This particular anchor is called a qiliq. The late Bill Pat Charlie of Chawathil First Nation, just east of Hope B.C., had one on the side of his house. Probably still there. The bottom criss crossed sticks made the anchor spin as it was being dropped intto the river, thus it caused the gang hook lines to spin as well thereby gaffing any passing salmon, usually chinook salmon. Gang hook lines were about 100 feet long, with a shorter line with a hook attached roughly every foot or so, and often 3 of them tied together when fishing in an eddy. Bill Pat Charlie and his grandfather used this method in all the eddys from Yale to Hope.

LikeLike

Naxaxalhts’i, wow, thanks so much – this is really fantastic information.

LikeLike

Agreed, thanks for the information. It’s challenging and very stimulating to think of an anchor as not being just a passive brute weight, but as having such a precise and active design element to it, and helps resolve in my mind why this one might be so carefully engineered.

LikeLike

I forgot to mention that the bottom criss crossed pieces starts out as one piece then with sharpened or pointed ends. Then it is split and crisscrossed with the flat sides facing upwards. It is the sharpened ends that make the anchor spin as it is dropped.

LikeLike

Aloha Northwest folks. I am a Hawaiian archaeologist & my colleague came across this fine grained basalt artifact found in Kenai, Alaska. I wasn’t sure how to post on your site so here is a facebook link to pic. Mahalo for your help

LikeLike

I have what I believe is a ancient anchor stone. It has a girdle in the middle to secure a cedar rope and petrogylphs depicting eyes at one end and

concentric whirls at each end. Photos available. eric peterson

petersons@uniserve.comnn

LikeLike

Hello Eric. The email you left bounced back. If you could email me a photo or a few photos at qmackie[at]gmail.com then I could give you an opinion and/or post them here for people to comment on…..

LikeLike

I have a stone anchor wonderfully modified to operate with great digging and holding ability. It is from the northwest

LikeLike